The Queer & Now – Final Project Summary

For my final project I chose to submit a project proposal for the Spring semester course. I’m proposing a project called The Queer & Now: Archiving Queer Internet Discourse in Contemporary Russia.

As it stands, there is no archive or otherwise research being done on the state of Queer discourse in Russia. Russia, as a nation which is in socio-political-economic turmoil at present, also has a history of being homophobic at the government level, which has only worsened in the wake of the war on Ukraine. Queer Russians are fearing for their lives, and due to the internet bans and other sanctions, many Queer Russians aren’t able to talk to the outside world to say what’s going on or ask for help. This project seeks to repair that.

The Queer & Now will utilize ARCH (Archives Research Compute Hub), a new platform by the Internet Archive currently in beta, allows users to create collections of websites, scrape and archive the data from them, analyze the data, visualize it, and download/disseminate the data all within ARCH. Luckily for us, I’m in the pilot test group and have early (and FREE) access to ARCH.

I intend on working with a small group of people to archive contemporary Queer discourse that occurs primarily on Russian websites, although we will likely also collect data from primarily English-speaking or international websites as long as the discourse is in Russian. Archival materials on Queer discourse post-AIDs Crisis, especially from non-English, is incredibly rare, and I’d like to change that.

This project will likely be ongoing after the Spring semester, as ARCH lends itself to repeating data scrapes, however this will take a lot of hard-drive space to store all the data and that is my most limiting factor.

Results will be published on GitHub and Quarto for public use. This data would be incredibly useful not just for social media dissemination to spread awareness, and not just for historical documentation purposes, but also for linguistic analysis and, of course, sociological and gender studies papers galore.

Final Project: More Than Surviving

Overview:

My final project delineates the proposal details of More Than Surviving, focused on Wampanoag social and political activities in the antebellum era (specifically 1830-50). Seeking to counteract the disappearing of Wampanoag from the retelling of the nation’s history and rectify the impact of the black/white racial binary, this project is will highlight the powerful acts of survival and social/political collaboration of the Wampanoag.

Northeastern Indigenous history is often limited to the colonial period. Historians have often focused enquiries and discussion to this time frame as it relates heavily to the founding of the nation, while Indigenous activists often highlight the misconceptions and the trauma and Indigenous perspectives of this period which historians often only approach via the European perspectives available in historical documents. More Than Surviving seeks to shift this perspective to focus on Wampanoag acts of self preservation and agency as well as showcase Indigenous presence in the Northeast beyond the colonial period.

Product

As a means to raise public awareness, the final project will both populate the timeline of Wampanoag political and social activism and activists between 1830-1850, a particularly active political timeframe nationwide, and map the activity to showcase ancestral ties. The online hub will be geared towards the general public, and in addition to the timeline and mapping, it will offer filters related to social/political issues (ex. Native Rights, Racial equality, etc.) and offer information about key individual actors where available. The issues chosen will overlap with national issues of interest to showcase the local and national implications of Wampanoag activism.

First Phase of Many

This project marks the beginning of a potentially long term investigation and sharing of political and social activity between the colonial period and today. Showcasing Indigenous activities decenters the colonial perspective and provides a valuable resource for building mechanisms to ensure cultural and community survival.

Final Project Proposal – Seminar Paper

Below is a copy of the final project proposal submitted earlier in the semester, followed up some updates text based on feedback.

For the final project, I plan to write a seminar paper on subquestion “b” as indicated in the final assignment, concerning problematic legacies, and tie the concept into how the digital humanities field continues to evolve. The question states: How do digital platforms/projects/tools evidence, retain, intervene in, or speak to unequal power structures that may be legacies of colonialism? In my paper, I plan to address unequal power structures in the forms of digital tools, mapping and various articles.

As part of my works cited, I plan to refer to the following readings and digital platforms:

Readings

- Digital Humanities: The Expanded Field – specifically the “Big Tent” metaphor, how we address structures of power, and how we should not have a US-centric approach to the field

- A DH That Matters – advocacy for marginalized communities, how our biases pervade technologies

- Making a Case for the Black Digital Humanities – who’s in and who’s out, what is foundational to the digital Black humanities

- Why Data Science Needs Feminism – the 7 principles of data feminism, specifically power

- Visualizing Sovereignty: Cartographic Queries for the Digital Age – imagining sovereignty beyond Western cartography, the map as a “technology of possession”

- The September 11 Digital Archive: Saving the Histories of September 11, 2001 – catered to a sector of victim’s families (does not include people who were racially profiled as a result of the attacks)

- Dividing Lines. Mapping platforms like Google Earth have the legacies of colonialism programmed into them – the connection between mapping and power

- Humanities Approaches to Graphical Display – Drucker urges us to not follow along with the assumptions of data tools, we must challenge them (question their meaning)

- Difficult Heritage and the Complexities of Indigenous Data – TBD

Digital Platforms

- Reviews in Digital Humanities – how accessible is the website? Who is being counted in the stats?

- The Invasion of America – https://www.youtube.com/embed/pJxrTzfG2bo

- Slave Revolt in Jamica: Brown argues that if we are to take seriously the opportunities afforded by digital forms of scholarship, we must remain attentive to how design and interface constitute modes of scholarly argumentation.

- http://revolt.axismaps.com/

- http://revolt.axismaps.com/map/

- Chicana por mi Raza – whose voices were / were not included

- Renewing Inequality – data included in the archive is not neutral and excludes important narratives

Next Steps

- As I continue to further develop this paper, I plan to add more resources to cite.

- Based on feedback:

- Frame an argument in a way that reveals a new problem / contributes to the conversation

- Provide an angle / opinion to the conversation, showcase voice

- Possible thesis: we are unconsciously biased and are therefore selective of the history we choose to archive – as a result, there are voices who are left out of the conversation as we continue to make this field (and society as a whole more inclusive / welcoming / less of gatekeeping).

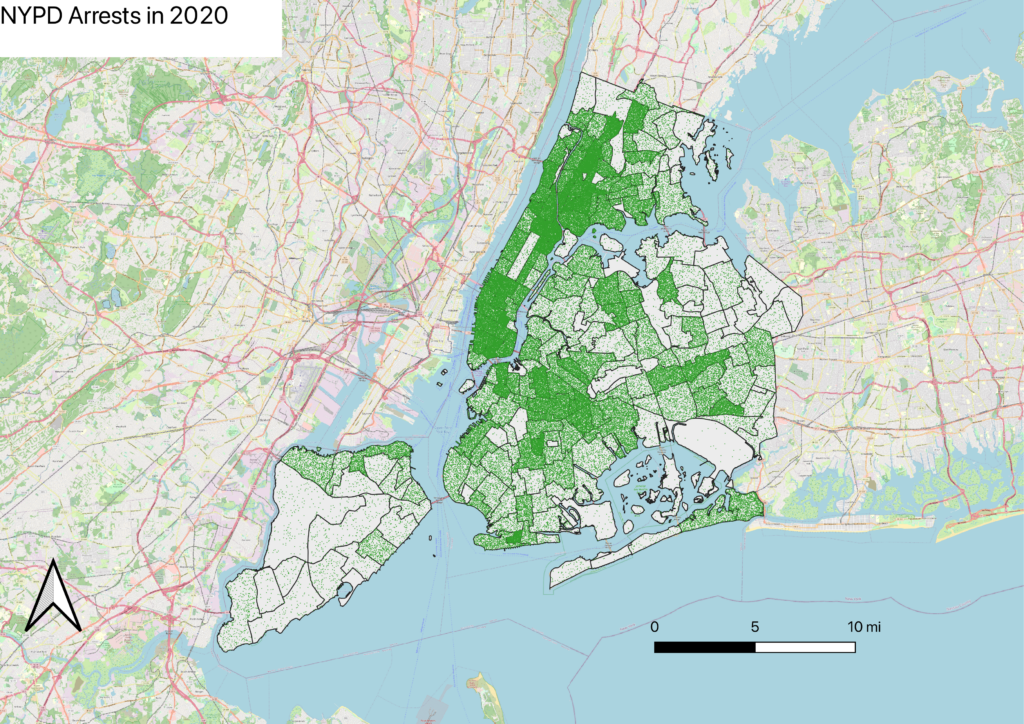

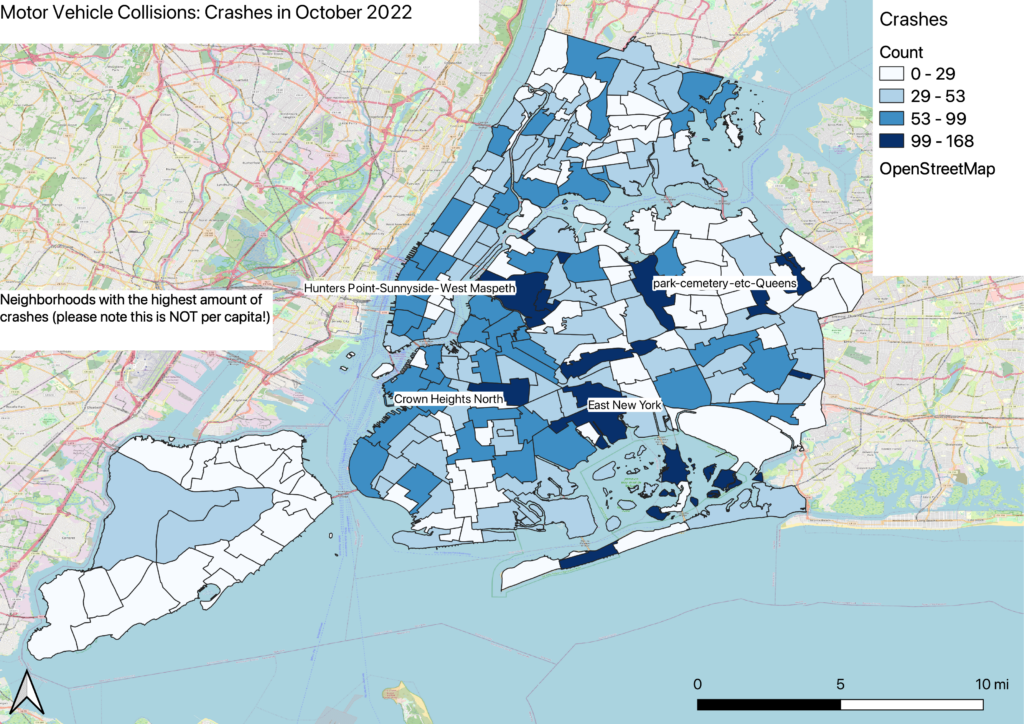

Praxis Mapping Assignment: NYPD Arrests and Motor Vehicle Collisions

Crime and motor vehicle collisions have been hot topic issues nationwide, especially since lockdown restrictions were lifted. In light of this event, I wanted to map NYPD arrests in 2020 as well as motor vehicle collisions in October 2022. Based on the GC Digital Fellows’ Finding the Right Tools for Mapping article, I elected to use QGIS to create both maps.

Both datasets were extracted from the NYC Open Data portal. For the NYPD arrests data, I chose to visualize 2020 arrests because I was curious to see if there was a change in the number of arrests prior to and post lockdown. As for the motor vehicle collisions, I elected to analyze the timeline of October 2022 because the dataset was too large to import into the program.

As stated in the article Finding the Right Tools for Mapping, some of the weaknesses of QGIS came to light while visualizing the data. I have a recent version of the program, and as a result, there were consistent bugs when applying multiple layers to the same map. In addition, without ArcGIS, I was unable to make the map interactive, and ultimately could not answer my initial question about the change of arrests pre and post lockdown. Lastly, I was fortunate to not have to geocode the addresses, but in the future I want to explore tools that give me that power.

Utilizing concepts from How to Lie with Maps, I chose a different map type for each dataset. For the NYPD arrests data, I chose a dot density format in order to visualize the distribution of arrests across NYC and to allow users to see which Census Tracts / neighborhoods contain the most arrests. Meanwhile, for the motor vehicle collisions data, I used a choropleth map because I wanted more control over the narrative of which neighborhoods had the most and least collisions. I quickly learned that an advantage of this technique is being able to distinguish the collisions among neighborhoods. However, since QGIS provides users with the ability to choose which scale to implement, I was able to use a scale that skewed the number of collisions — this is where Monmonier’s term of “lying with maps” comes into play.

In the future, I would like to incorporate ArcGIS to make both maps more interactive. In addition, I would like to import more of the motor vehicle collisions data and illustrate a timeline of how the number of crashes have changed over the past decade.

Summary of Final Project Proposal-Peter O.

Project name: Borough of Churches Online: Mapping Brooklyn’s Houses of Worship, 1898-2022

Proposed digital product: A website featuring a primary ArcGIS map displaying all extant, converted to other use, and demolished church buildings within the Borough of Brooklyn between 1898 (the year of Brooklyn’s incorporation into the City of Greater New York) and 2022, supplemented by maps displaying decade-by-decade views (1898-1907, 1908-1917, etc…)

Audience: This project would be of use to scholars of urban religion, history and sociology investigating a range of questions related to church demolition over time and the effects of this activity on local communities, and would be of general interest to public historians, journalists, students, and preservationists.

Existing models: Existing projects using mapping to study sacred space in the urban landscape tend to lean toward one or another pole in a balancing act between displaying data and telling stories: the needs of a robust reference tool, characterized by geospatial and descriptive precision in the display of a data set as broad and inclusive as the extant sources allow, must be balanced with the needs of user engagement, achieved through selective storytelling by textual, visual, and audible means. The initial phase of the project proposed here focuses on the creation of a reference tool, but hopes to expand into a platform featuring blogpost-style stories and immersive uses of audio and video recordings in future versions.

Groundwork: The most crucial factor in the success or failure of this project hinges on the creation of an original geospatial dataset of the locations of extant and demolished churches based on rigorous historical research into ecclesiastical records, newspapers, municipal (Department of Buildings) records, old maps, and other historical sources and secondary literature on the topic of religious and social life in Brooklyn. This data will then be converted into geospatial data, plotted on the maps described above, and hosted on a content management platform (Drupal, WordPress).

Limitations of the current proposal: The ‘historic’ churches included in this project will most likely be limited to current and former properties of established Christian denominations with presences in Brooklyn dating to at least the early twentieth century, for which useful public and institutional records are most likely to exist, and from which a manageable data set could be established. Regrettably, this risks excluding independent Christian churches and other religious organizations operating out of storefront properties or private homes for which historical data might be lacking, for example former meeting places of Black/African American worship, some of which might not be represented in the sources of the Anglo-American written record.

Potential issues for long-term maintenance and access: Even though it is not an open-source software, I selected ArcGIS for its ability to create popup textboxes to display information, a feature vital to this project. A funding source for the future renewal of licensure would need to be determined.

Workshop Recap: Fair Use

This recap of the Mina Rees Library’s Fair Use workshop is a little belated; Tomiko already reviewed the follow-up workshop on Creative Commons. However, I’ve been reflecting on it as I work on my final project, and I thought some of the takeaways might be helpful for others as they gather materials, now or in the future. The workshop was led by Jill Cirasella, an Associate Professor and Associate Librarian for Scholarly Communication; I’m happy to email any of you some follow-up resources she shared after.

The main thing that stuck with me is that Fair Use (like so much we deal with in the humanities!) is nebulous and open to interpretation. If you follow music industry news and controversy, you probably already know that the line between sampling or inspiration and copyright infringement is a thin one, and reasonable people (and their lawyers) can disagree on where exactly it is.

Professor Cirasella took us through the historical and legal basis for Fair Use in the United States, starting with the Constitution, which provides a foundation for the concept of copyright:

“The Congress shall have power… to promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.”

United States Constitution, Article 1, Section 8

The reasoning behind this right — “to promote the progress of science and useful arts” — is key to understanding Fair Use and how it provides a small loophole * (not a legal term! Please research this for yourself!) to allow for use of copyrighted work while the copyright is still in effect. (Which, by the way, is a long time.)

Here’s how Fair Use is defined in U.S. law:

“[T]he fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies … for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include—

(1) The purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

(2) The nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) The amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) The effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

17 U.S. Code § 107, via Cornell Law’s Legal Information Institute

The four factors listed can help you determine whether something is Fair Use. (This page from Columbia University Libraries goes into more detail about these factors, including how the courts have ruled based on each.) The history of case law related to Fair Use can also help you determine whether a potential use qualifies — although it’s complicated, the good news is that the rulings in these cases have generally expanded the scope of Fair Use has over time. As we learned in the workshop, Fair Use grew to cover home recording of televised events (Sony v. Universal, 1984), parody (Campbell v. Acuff-Rose/2 Live Crew, 1994), and transformative use, as in the case of Google Books, which has digitized books in order to make them searchable without sharing the full text (Authors Guild v. Google, 2015).

The takeaway? Using material for teaching is usually Fair Use, especially if you’re mindful about how much of a copyrighted work you use. For creative projects, it often depends on what you’re doing with it — how transformative it is, how much you’re using, and whether your use makes the original worth less. For example, it would be hard to argue that a parody, like Weird Al’s “Amish Paradise,” makes people less likely to listen to or pay for Coolio’s “Gangsta’s Paradise” — which in turn, heavily samples (with permission) Stevie Wonder’s “Pastime Paradise,” which didn’t necessarily lose value either.

I’m no expert on Fair Use, but the library workshop has given me a better sense of what it covers and why, as well as some tools to help determine whether a potential use is or isn’t fair. I’ll leave you with one I’ve found particularly helpful: this Fair Use checklist from Columbia University Libraries.

Finally, if you didn’t make it to a library workshop this semester, I’d highly recommend it. The full calendar is here.

Final Project Overview – Energy Consumption Map

In this blog post, I’d like to share my idea for the final project, which would be a grant proposal.

Name: Renewable Energy Consumption Forecast Map (still WIP!)

Product format: Website with an interactive map

Abstract: The grant proposal for building a web app hosting a dynamic and interactive map that shows energy consumption forecasts. The website will also include basic calculations and simulations to help consumers estimate energy usage, cost, and credits.

Context: One of the key challenges for transitioning from fossil fuel to renewable energy is managing the energy grid (as supply and demand fluctuate). Fossil fuel supply can be very predictable (you can burn as much as you need). Unlike fossil fuel, Renewable energy (along with the storage challenge), there’s kind of a “cap” on production. The only way to increase production is to have more hardware such as solar panels (which we must remember they not that sustainable to begin with, it also doesn’t make sense to have 100 additional solar panels just to cover the peak usage of 2 summer hot days).

Problem Space: Managing supply and demand for renewable energy

Why does this matter: Managing supply and demand in an agile manner is obviously necessary for fossil fuel to the renewable energy transition. However, doing it in a socially-just manner could be pivotal in rebalancing power between the energy companies and the consumer. Considering Environmental and Climate justice tends to distribute both advantages and disadvantages unfairly to marginalized communities. This is important to keep in mind that we should not simply aim to transition from fossil fuel to renewable energy, we also leverage this moment to address environmental and climate injustices. After all, it will be unfortunate if we do successfully transition away from fossil fuel, but all the energy companies are still in a position of power that would allow them to place profit before people.

Current solution: Consumer-facing levers for demand management: Increase pricing to reduce demand (aka peak hour surge pricing)

Proposed additional solution: Incentivizing households to reduce electricity usage at peak times when demand is at its highest, by offering energy credits or cash rewards. The rationale behind this idea is that households should get “rewarded” for saving energy during these peak hours and thus make them more available for the rest of the grid.

What do we need to make it happen: Transparency of energy usage as a foundation of information sharing and a place to tackle market dynamics where incentives can be mobilized –> a website with energy consumption and reward calculator.

Text mining Praxis

We did the assignment recently for another class and I just to import it here since it concerns the text mining in particular. It was a group project and the text we chose was the time classic Dracula right around the Halloween. It was an annotating assignment but the text mining was important part of it. Our group took this text and we ran through the Voyant text mining program to find out which words were most used in this novel. The usual words such as vampire, time, etc were present but some were very interesting to say the least such as room or poor (which in Victorian times were ever present theme).

Text mining and text analysis are good tools since they save your time. I just imagine a time for Digital Humanists to comb through the novel hand by hand to count each words and tally them to get the whole picture. These types of assignment and exercises would not be even possible say couple of decades ago. These programs provide us a new tools to analyze the novel in more nuanced ways and find which rhetoric was employed in the novel. I want to bring in the works of Ian Bogost’s term of procedural rhetoric in analyzing the novels since we can infer the laws of that world through analyzing the words that are used in this Victorian novel.

There are a lot of words concerning communication in this novel and if we break down the novel using the definition of procedural rhetoric we can infer some things. Things such as communication pre 20th century was based on good listening, availability of candlelight and the prominent usage of letters for example since it is written in the late 19th century. A good handwriting was paramount and we start to understand the “laws” of that setting in more nuanced ways and the text mining give us the tools to explore them.

Deconstructing the text or any other media are important in understanding the building blocks of these works. These tools are convenient and powerful at the same time. They save time, and present an appealing platform to be digested by people who may not be tech savvy.

The Metaverse and the Perils of Technopositivism

In our discussion of Alan Liu’s essay, Where is Cultural Criticism in the Digital Humanities? last week, my group circled around the other topics that were raised in this week’s readings — professional roles in the academy, the economics of the university, and of course, the metaverse and its role in education.

This passage from Liu’s essay speaks to what I’ve found missing in most discussion of the metaverse, including this week’s readings (emphasis mine):

While digital humanists develop tools, data, and metadata critically, therefore (e.g., debating the “ordered hierarchy of content objects” principle; disputing whether computation is best used for truth finding or, as Lisa Samuels and Jerome McGann put it, “deformance”; and so on) rarely do they extend their critique to the full register of society, economics, politics, or culture. How the digital humanities advances, channels, or resists today’s great postindustrial, neoliberal, corporate, and global flows of information-cum-capital is thus a question rarely heard in the digital humanities associations, conferences, journals, and projects with which I am familiar.

This introduction to learning in the metaverse acknowledges that immersive “technologies remain more expensive than other learning resources such as computers and books” and “content is more expensive to create” but doesn’t proceed further to ask how mediating not-for-profit learning through a technology that requires extensive financial resources might affect which ideas and arguments are and aren’t taught (unsurprising, since despite the academic bona fides of some of the authors, this text is published by a “storytelling and experiential agency” that touts its partnerships with Meta and Lenovo). It also raises a question that’s troubled me for a long time. With the rise of corporate educational technology, who controls learning outcomes and practices: educators or corporations?

For instance, take this ad from Meta, Facebook’s parent company. It’s worth watching if you haven’t seen it, because it illustrates what I see as the dangers of the metaverse:

The possibilities are endless! Except… each of the possibilities depicted here contains and creates its own limitations and barriers. The field trip to ancient Rome sounds amazing! But…

- Even without the need to purchase headsets, the creation of such a thing would be fantastically expensive: actors, subject matter expertise, scripting, computer-generated settings, and QA all cost money. Who would pay to create it, and what might they privilege because of their own bias or cut to save money?

- If AI were used to generate some of the simulation and cut costs, whose work would be used to “train” the AI, and would that person be compensated? And would the final project hold up to academic and historical scrutiny?

- Would schools pay to access this type of simulation? If so, what would be cut from the budget in exchange? If not, what would students be “paying” to get such a simulation for free? It’s easy to imagine a conservative think tank funding curriculum on the Classical world — what biases would that introduce?

- What would be the educational opportunity cost in terms of time and focus? What might be cut (either from the curriculum as a whole or the discussion of this specific topic) based on pressure to make the most out of an expensive, shiny new tool?

- How can the educational value of such an experience be measured, and if it’s found lacking, will there still be pressure to use a metaverse field trip because of sunk cost? This article we read on the educational benefits of immersive virtual reality found better outcomes for students who accompanied Al Gore on a VR trip to Greenland than for those who just watched a video, but do these outcomes translate to situations where students are expected to apply deeper critical thinking skills or synthesize information to make an argument?

Similar questions could be raised about every example mentioned in the video. For instance, it seems like a neat trick to let a farmer visualize the spots in his field that need more water, until you remember:

- Agricultural knowledge and experience allows farmers to do just that on their own, and

- That knowledge is disseminated in a variety of ways, both informally/traditionally, and through public universities with agricultural programs, which have their own traditions of scholarship, political and humanistic thought, and engagement with the wider agricultural community, and

- Once a farmer has that knowledge, they don’t have to pay a subscription fee to use it or share it with others.

In this way, metaverse education can be seen as furthering the 20th-and-21st century corporate project of taking something that once belonged to no one and everyone and making it into a source of profit (see: Disney’s transformation of folk fairy tale plots and characters into copyrighted IP). The farmer no longer owns the ability to evaluate their fields. Teaching about ancient civilization means one thing — a glossy VR field trip — rather than a multitude of possibilities depending on student interest, teacher knowledge, and pedagogical goals.

Let’s go back to Liu and his argument that digital humanists who don’t “extend their critique to the full register of society, economics, politics, or culture” aren’t truly engaging in humanities work. Any effort toward an “educational metaverse” is inherently political, as the technical and logistical requirements of creating highly complex edTech mean that power, resources, and cultural hierarchy will always play a role in determining what’s taught and how. Any discussion of the metaverse that isn’t grounded in that reality is uncritical technopositivism — and not truly based in the humanities.