Project name: Borough of Churches Online: Mapping Brooklyn’s Houses of Worship, 1898-2022

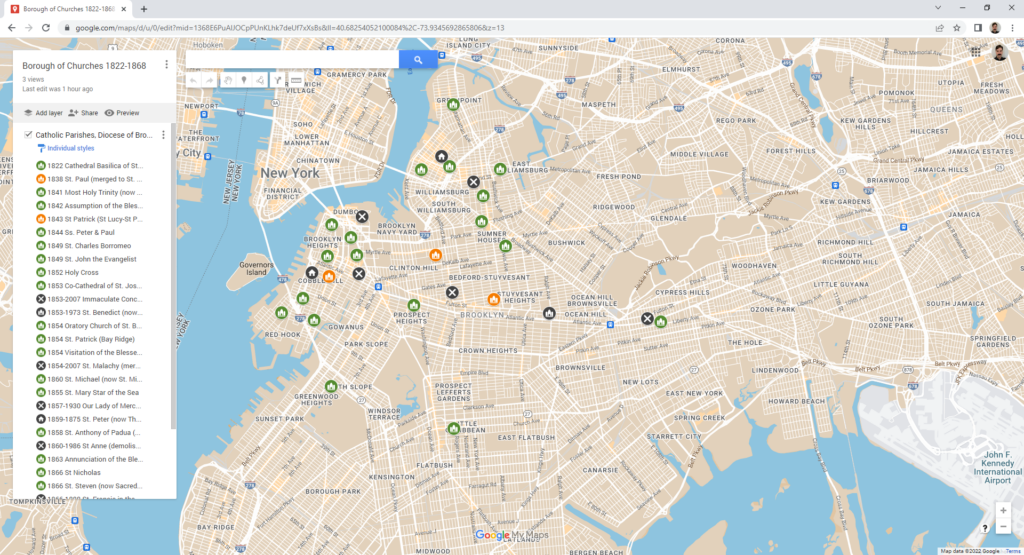

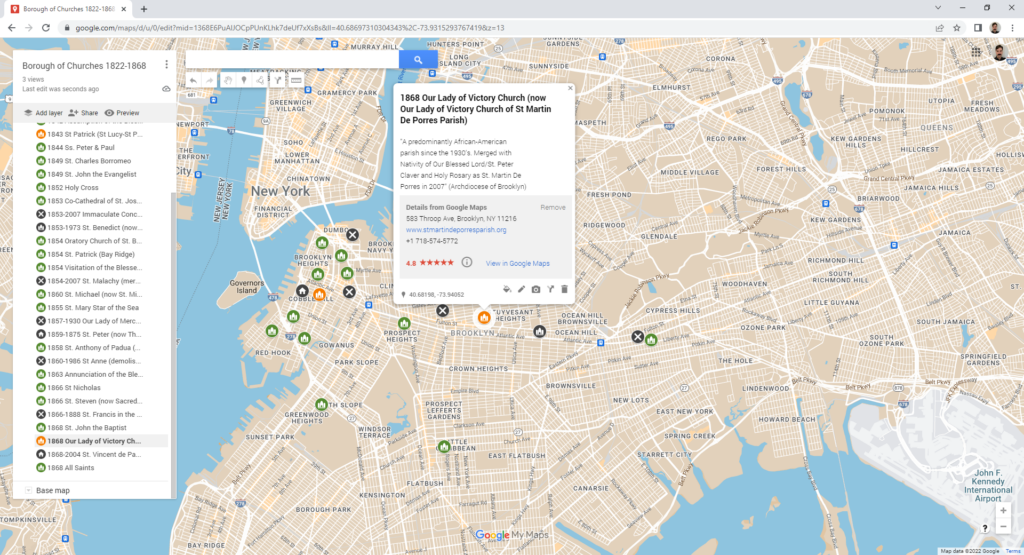

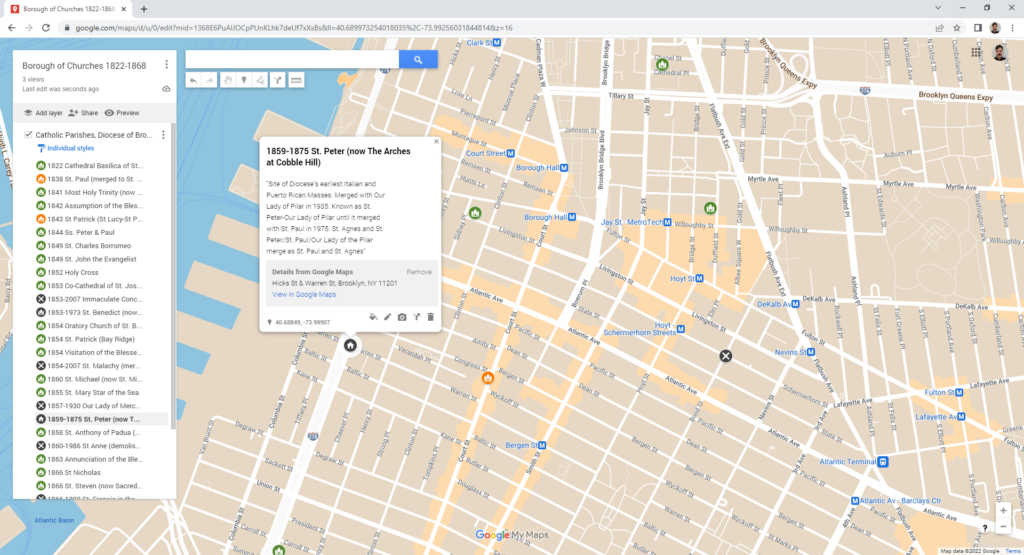

Proposed digital product: A website featuring a primary ArcGIS map displaying all extant, converted to other use, and demolished church buildings within the Borough of Brooklyn between 1898 (the year of Brooklyn’s incorporation into the City of Greater New York) and 2022, supplemented by maps displaying decade-by-decade views (1898-1907, 1908-1917, etc…)

Audience: This project would be of use to scholars of urban religion, history and sociology investigating a range of questions related to church demolition over time and the effects of this activity on local communities, and would be of general interest to public historians, journalists, students, and preservationists.

Existing models: Existing projects using mapping to study sacred space in the urban landscape tend to lean toward one or another pole in a balancing act between displaying data and telling stories: the needs of a robust reference tool, characterized by geospatial and descriptive precision in the display of a data set as broad and inclusive as the extant sources allow, must be balanced with the needs of user engagement, achieved through selective storytelling by textual, visual, and audible means. The initial phase of the project proposed here focuses on the creation of a reference tool, but hopes to expand into a platform featuring blogpost-style stories and immersive uses of audio and video recordings in future versions.

Groundwork: The most crucial factor in the success or failure of this project hinges on the creation of an original geospatial dataset of the locations of extant and demolished churches based on rigorous historical research into ecclesiastical records, newspapers, municipal (Department of Buildings) records, old maps, and other historical sources and secondary literature on the topic of religious and social life in Brooklyn. This data will then be converted into geospatial data, plotted on the maps described above, and hosted on a content management platform (Drupal, WordPress).

Limitations of the current proposal: The ‘historic’ churches included in this project will most likely be limited to current and former properties of established Christian denominations with presences in Brooklyn dating to at least the early twentieth century, for which useful public and institutional records are most likely to exist, and from which a manageable data set could be established. Regrettably, this risks excluding independent Christian churches and other religious organizations operating out of storefront properties or private homes for which historical data might be lacking, for example former meeting places of Black/African American worship, some of which might not be represented in the sources of the Anglo-American written record.

Potential issues for long-term maintenance and access: Even though it is not an open-source software, I selected ArcGIS for its ability to create popup textboxes to display information, a feature vital to this project. A funding source for the future renewal of licensure would need to be determined.