For my text analysis assignment, I decided to use Voyant to look at one of the English language’s great historical works: The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by Edward Gibbon, published in six volumes (further divided into 71 chapters) over thirteen years from 1776 to 1789. Gibbon’s magisterial study spans a period of over 1,300 years, examining the Roman-Mediterranean world from the height of the classical empire to the fall of Constantinople, capital of the eastern Roman empire (which western authors have anachronistically called the ‘Byzantine’ empire since early modernity), to the Ottoman armies of Mehmet II in 1453. Gibbon’s scholarly rigor, sense of historical continuity, and dispassionate, meticulous examination of original, extant sources contributed to the development of the historical method in western scholarship. Nevertheless, some of Gibbon’s conclusions in the Decline and Fall are also a product of the eighteenth century in which the author lived and wrote, and Gibbon’s writing is occasionally punctuated with moralizing statements (briefly touched on below).

The majority of text analysis experiments seem to focus on works of fiction, paying particular attention to their stylistic and aesthetic dimensions. I asked myself: what about an historical work, which is also a narrative construction? Would running Decline and Fall through Voyant allow a reader to observe trends in the stylistic or moralizing dimensions of Gibbon’s grand historical narrative, beyond what might already be grasped by an ordinary reading the text? (disclosure: I have by no means read all six volumes of Decline and Fall in their entirety).

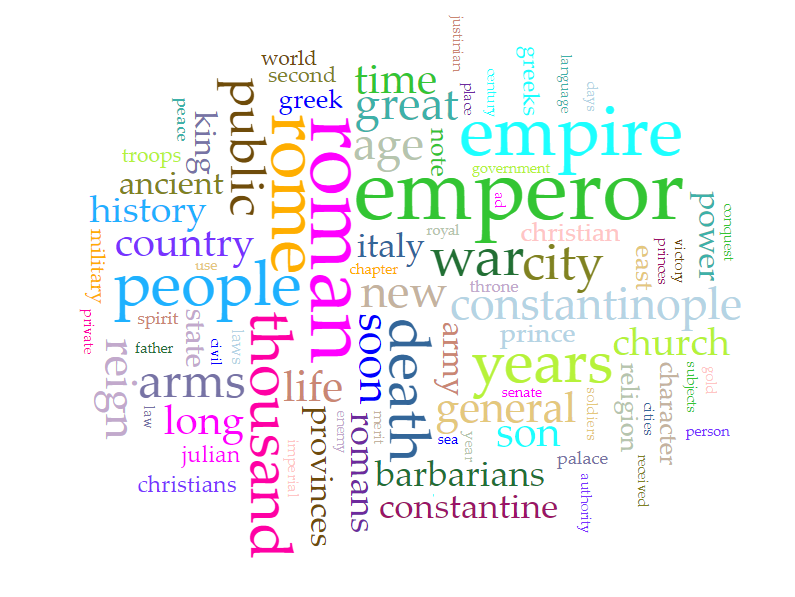

I used a plaintext file of Decline and Fall from Project Gutenberg that features an 1836-45 revised American edition containing the text of all six volumes. Prior to uploading this file in Voyant, I removed the hundreds of instances of the word ‘return’ in parentheses (which in the HTML version of the file link to the paragraph location in the text), in addition to the preface and legal note at the end of the work authored by Project Gutenberg. After uploading the file, I added additional stopwords to Voyant’s auto-detected list. The terms I removed relate to chapter headings (e.g., Roman numerals), citations (‘tom’ for tome, ‘orat’ for oration, ‘epist’ for epistle, ‘hist’ for historia’, ‘edit’ for edition and so on), and occasional Latinate (‘ad’, ‘et’) and French (‘sur, ‘des’) words. To this end, the word cloud tool was helpful for identifying terms that should be added to the stop-word list.

The resulting word cloud was, to say the least, neither surprising nor particularly revealing nor useful, most of the terms referring to the work’s predominant subjects:

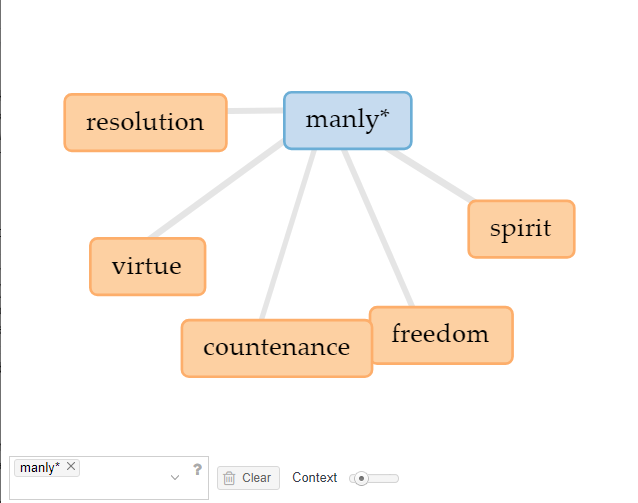

Standing out as one of the only abstract terms visible in the cloud limited to the top 75 words, however, was “character,” with 828 occurrences. Navigating to the ‘Contexts’ tab, I generated a concordance displaying instances of ‘character,’ which revealed a plethora of specific adjectives used in Gibbon’s text, for example, “manly.” Running ‘manly’ through the ‘links’ generator reveals a network of terms that reflect classical Roman definitions of masculine virtue (‘virtue,’ ‘spirit,’ ‘resolution,’ ‘freedom’) and one usage related to physical appearance (‘countenance’):

These results are once again neither surprising nor interesting, since the ancient (male) writers informing Gibbon’s work were themselves concerned with writing about the meritorious qualities and/or vices of individual male leaders for moralizing, didactic purposes, be they emperors, generals or bishops. This calls to mind Michael Witmore’s observation that “what makes a text a text–its susceptibility to varying levels of address–is a feature of book culture and the flexibility of the textual imagination” (2012). These particular examples may demonstrate the influence of classical authors on Gibbon’s narrative, but they do not necessarily convey anything about what is original in Gibbon’s prose (or, differently stated, original to Gibbon’s contemporary setting).

Perhaps one could get closer to an analysis that better reflects Gibbon’s original, polemical thesis and writing style by first 1) identifying a comprehensive list of moralizing terms (including adjectives like ‘superstitious’ and its variants) harvested from the whole text, and then 2) analyzing the occurrences of those terms in the text, and 3) looking for trends in how those terms are employed throughout the text to describe different social, ethnic, religious or occupational groups. As an enlightenment scholar critical of organized religion, Gibbon maintained that the rise of Christianity led to the fall of the western empire by making its denizens less interested in the present life, including in things civic, commercial, and military, the latter of which would have obvious consequences for the defense of the empire against invasion (Gibbon’s thesis is not generally shared by scholars today). Would such an experiment reveal more exactingly where Gibbon’s moralizing emphases change, based on the chapter or volume of the text where such terms occur?