THIS WEEK, as I was analyzing a specific DH project, the following aspects of our readings provided a lens of investigation.

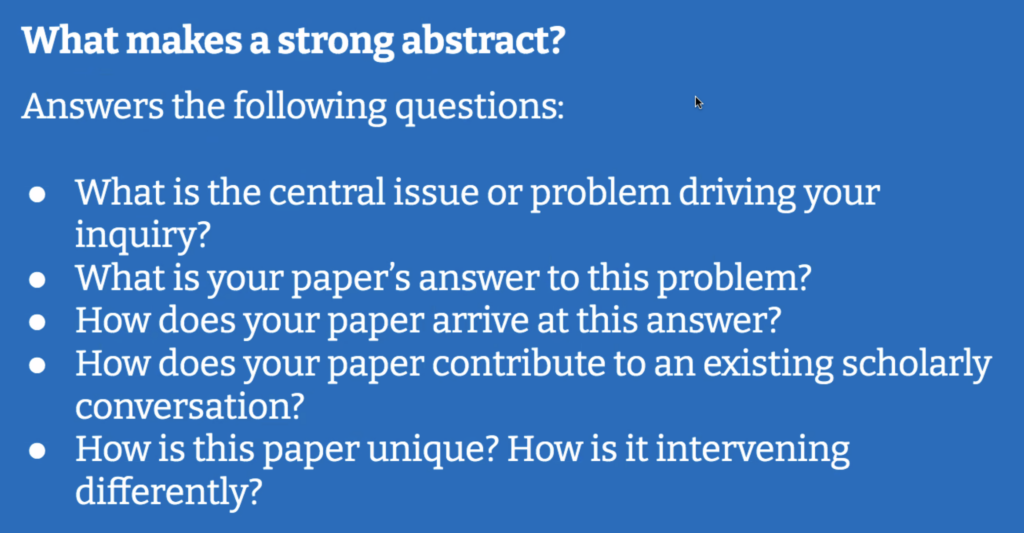

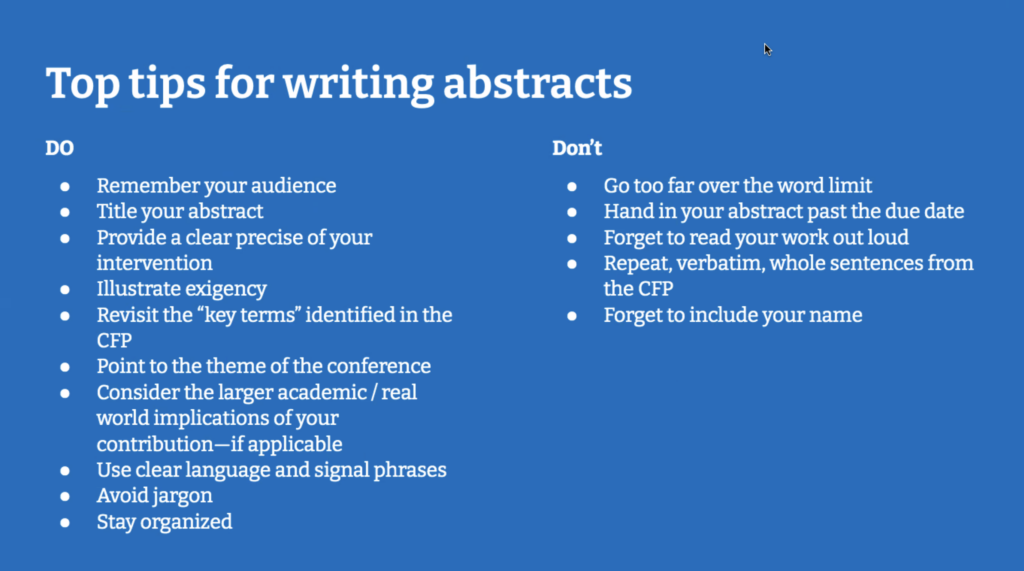

- The discussion in Ramsay’s and Rockwell’s text about what constitutes scholarship and whether there is a way to have scholarship without the “discursive elements” – the question of whether a prototype can be theory? Can a thing be scholarship without discourse that illustrates, and articulates the maker’s thinking about the thing?

- And the above text’s intersection with Presner’s call for a more expanded definition of critical discourse. Presner notes the field’s obligation to consider and widen what critical theory encompasses. He especially advocates for critical theory to consider and expand into that “which might or could be”, the utopian.

So, above, we have one argument for questioning the reliance on traditional scholarly discourse as a necessary ingredient of scholarship, and one argument for leaning more into the potential of critical discourse and expanding its place in scholarship.

Adjacent to these seemingly conflicting considerations, I also felt that …

- …the distinction between qualitative and quantitative data underlined in D’Ignacio and Klein’s work on Data Feminism plays an important role in considering what is legible (for what reader?) as scholarship, esp. if it is presented without much explanatory or interpretive discourse. Here, their footnote 42:

“People often say that there are two broad kinds of data: quantitative data, consisting of numbers (e.g., how many siblings you have), and qualitative data, consisting of words and categories (e.g., what color is your shirt?). As we will show in chapter 4, any time there is a binary, there is usually also a hierarchy, and in this case it is that quantitative data can be incorrectly perceived as “better” than qualitative data for being more objective, true, generalizable, larger scale, and so on. Feminist researchers have consistently demonstrated the need to collect qualitative data as well, as they can often (but, of course, not always) capture more nuance and detail than numbers.”

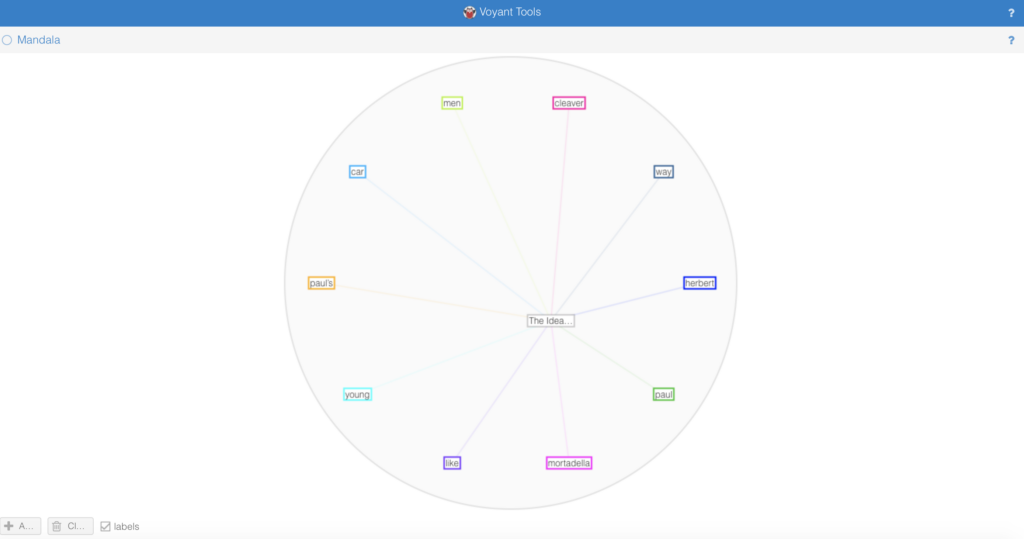

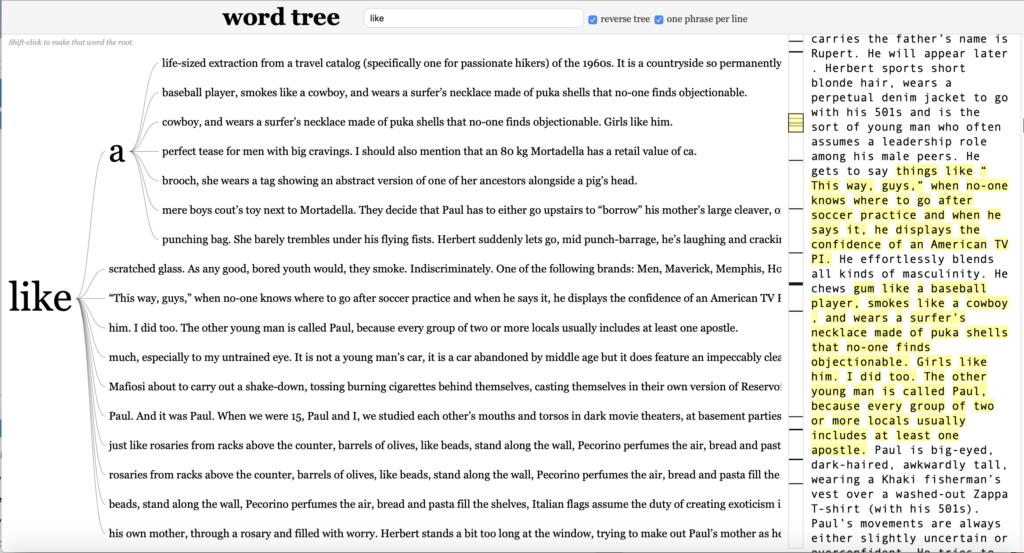

The lens these three observations created, made me look at how specific DH projects integrate discursive context and how leaning on qualitative vs. quantitative data might influence the presence or absence of traditionally scholarly context. I finally chose to take a closer look at a DH project “To See or Not to See“ – an Interactive Tool for the Visualization and Analysis of Shakespeare Plays that seemed to present itself directly to the user/reader without much context.

[Full disclosure: I also chose this because my academic journey began in theater history, I trained and worked as an actor and a playwright, and I continue to create work for the stage that investigates collisions of stage and screen.]

Here is the link to the project’s page, specifically the page for Hamlet: http://www.thomaswilhelm.eu/shakespeare/output/hamlet.html

Essentially the project turns the plays’ text into quantitative data (counting words and lines) and then colorcodes which character/speaker is associated with the text. It shows one entire play on one “page.” Even at first glance we can already see how much stage time (i.e graph space) each character’s text occupies. We can get a sense of the characters’ movement through the story and easily track their (especially the protagonists’) arcs.

WHAT DATA IT WORKS WITH:

The project works with a stable and finite data set: The Shakespeare Folger Editions text (via the Folger Editions archives). The Folger text of Hamlet, e.g., is very likely complete and will not change. So, questions of accommodating growth don’t have to be central for the creators.

The project focuses exclusively on the quantifiable aspects of Shakespeare’s play, i.e., the countable aspects of language , word- and lines counts.

Which already brings up the question of what it doesn’t work with. (See the last section of this post.)

WHAT IT LOOKS LIKE:

As many other data visualizations I encounter in my daily reading life, the overall structure of this project takes full advantage of our familiarity with interpreting a grid. The x-axis traces the play from beginning to end, leaning on what Kurt Vonnegut illustrated when he proposed that all stories could be turned into graphs. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oP3c1h8v2ZQ )

The y-axis lists the play’s characters, likely in order of total time present, or perhaps in order of relevance in relation to the protagonist. But there is also an implicit – or is it explicit? – arrangement by class (Royals at the top). This organization is a replication of a familiar hierarchy – which contributes to an easy the “reading” experience and yet perpetuates and fortifies problematic structures.

Giving the characters distinct color coding helps to trace text data ascribed to them. The color schemes don’t telegrapgh a methodology and seem more intent on easily showing contrast.Each character is represented by name and a male or female gender symbol, which says perhaps more about what data the authors anticipate readers will want to parse than it says about the world of the play or theatre at the time of Shakespeare.

Additionally, and especially interesting although easy to skip, is a band at the top, that traces the play’s non-dialogue text – i.e.its stage directions, entrances, and exits.

Beyond the main screen, there are two pop up windows which let the user delve deeper into the quantifiable elements of the play. The pop-up windows show a) SPEECH: sections of dialogue that are tagged to indicate modes of text (like speech, song, quote etc.) and b) METRICS: graphs that present the network and data specific to the character. For example, I can see all characters Ophelia interacts with, how much she interacts with them, and how her dialog-quantity compares to the play’s overall word-count and a selected act’s word count.

Together, the data show the underlying webbed structure of the play’s world and it’s inhabitants’ relationships.

WHO MADE IT:

Information about the project, adjacent scholarship, and its makers is hidden within the ‘about’ section of a small gray menu button. In other words, it’s not prominent. A link to a scholarly paper is part of the about page. The short paper is a traditionally scholarly text, and the way to discover the names and affiliations of the authors: Thomas Wilhelm, Manuel Burghardt, and Christian Wolff – likely three German men affiliated with a German University. (Sidenote: German theater has a deconstrionist attitude toward Shakespeare’s plays. The plays are often cut and rearranged according to the director, so it strikes me as interesting that a project that so clearly appreciates the full text emerges there.)

WHAT IT’S LIKE TO READ/USE IT:

The visual impact of the entirety of Hamlet one one screen equals the satisfaction one can feel when looking at a good map of a city one has lived in.

It works as a tool (a response to our desire yet inability to grasp more extensive chunks of time and space) that facilitates orientation. There is certainly new knowledge in understanding space and time of Hamlets 2+ hour universe from a bird’s eye view/on one single image. As each play is creating a world of its own, these data collections might function as maps/guides through a Shakespeare imagined universe.

The structure and provided data are easy to navigate and understandable for those who has encountered the play before and have an initial familiarity with Shakespeare’s drama. The authors’ assumption is definitely that their users have a familiarity with Shakespeare and that a quantitative look at a text might yield insight beyond traditional, literary text analysis.

It’s not intended as an introduction to Shakespeare, I don’t think. So, the assumption of a knowledgable readership obviates the need for a user manual or how-to guidance — at least at first glance. In the related paper, the authors confirm this assumption about audience. They imagine the site to be of use for people working in or creating work about theater.

And it is.

I made my partner, who’s a professional actor, look at the web-site, and she was instantly enthusiastic about the possibility it might afford her when preparing for a role. As an actor the aspect of a play that stays ambiguous the longest, is a sense of the entire arc one’s character travels. Grasping the arc is necessary in crafting the performance, so having a tool that makes a particular arc so visible, would likely help an actor by illustrating a characters place in the play’s eco-system quickly and succinctly. A theater director who is in the process of shaping the staging of the play, could find this map invaluable as well. The authors also imagine that it could inspire new points of entry for literary analysis, by showing, e.g., word-quantity disparities between genders.

So what makes this project effective is the author’s understanding of potential users and how little context these users need to grasp the project’s application and implication. It presupposes an informed/partially informed reader with a specific goal and can therefore leave more unarticulated.

And still, when I read the related paper, I was grateful for the ways in which it helped me to move beyond my initial evaluation of the project’s possibility. In that way, a theoretical discourse does become necessary. The paper did inspire me to think more creatively about the project’s uses and suggested applications beyond my familiar realm. I almost wish that aspects of the paper, in less formal articulation, could preface the project or even interrupt it.

QUESTIONS THAT REMAIN:

I understand that quantifying an experience (theater) and a literary work (play) is intriguing. Quantification seems to offer a path toward understanding and parsing how and why art works for humans. (And I also understand the reverse. How often it is important to find the story data tells via using a unique narrator’s take on the data.)

However, theater as an experience still centers the qualitative and subjective. Where do these aspects go in the analysis of world-count?

How to mark up/count a catharsis? Is there a discomfort with the ambiguity of qualitative aspects? Does it force a thinking about the variety that performance might bring to these texts? (What about tone, subtext, intention that imbue the words?) What are these aspects so resolutely excluded?

What are the implications and limits of the structure-the reflexive absorption of the grid? What metrics are left out? Considerations of plays shown in repertoire by a company, men playing women’s roles, identity markers other than gender? How would these considerations interfere with the binaries established by the grid?

The creators talk about possible expansions of the project. How do the current discoveries they have made help facilitate new discoveries? Or is it possible the current direction keeps us from entering a radically different but equally productive line of inquiry?

Finally: A bit of a meta question, related to my interest in narrativity. Does it entrench the view of “story” as a hero’s arc and how does this quantification relate to notions of narrativity?