In my opinion, there has and never will be a true “definition” of DH as it in itself is an art and with art, there are many passages and pathways. However, I do think it can help captivate audiences and bring not only an opportunity but knowledge to those universally. For example, The Digital Black Atlantic brings a more “inclusive term “digital Black Atlantic” into the light from the very root, Digital Humanities. But, what is the “digital Black Atlantic”? Well, Josephs and Risam (2021) beautifully defines it by saying,

“In the space between “digital” and “humanities” where Blackness and technology meet, the digital Black Atlantic pushes back against the ways that technologies have historically been and continue to be used to disempower Black communities (and also against the dominance of such narratives) to instead emphasize how Black communities have taken advantage of the affordances of technology to assert their humanity, histories, knowledges, and expertise.”

Josephs and Risam (The Digital Black Atlantic 2021)

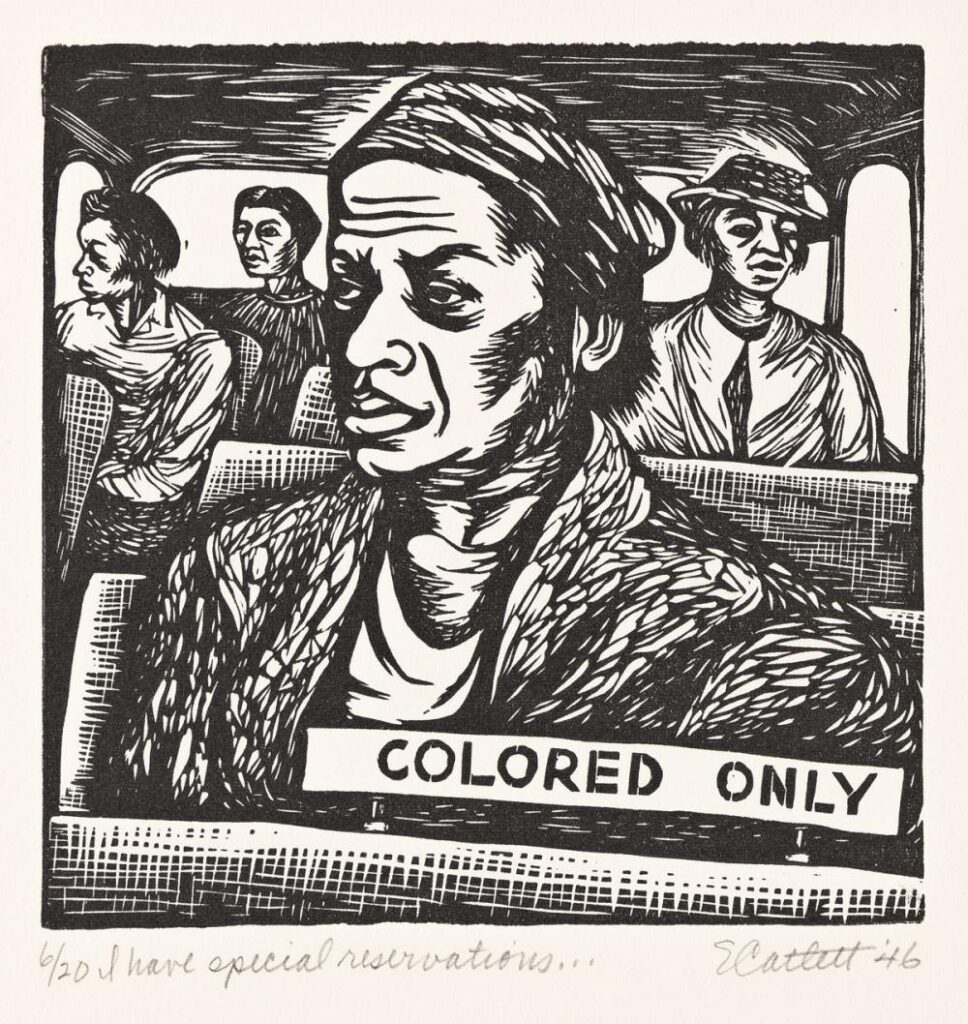

This leads me to one project that captivated me, Colored Conventions Project. Representing past and present socio-economic and racial issues, in which I feel that DH can have a strong representation in both. This representation being, showing and giving knowledge to others about issues whether it be nationally or universally. Uncovering “buried history” is not only important for the families that had to live through it but for the future.

Relating this to my current (and many) definition(s) of DH, art can be constructive, knowledgeable, collaborative, and even political etc. Art signifies history more than we know, and bubbles important issues for all to see. The “digital Black Atlantic” unites all from accross the world to understand not only American Black history but brings representation to the bigger moral dillemma of race. The CCP unites DH and their organization to bring “scholarly and community research project dedicated to bringing the seven decades-long history of nineteenth-century Black organizing to digital life.” by using “innovative, inclusive models and partnerships to locate, transcribe, and archive the documentary record related to this nearly forgotten history and to curate digital exhibits that highlight its stories, events and themes.” (CCP 2020).

Source: invaluable.com