Re: Analysis of a Digital Humanities Project and Lightning Talk

The first thing I noticed when researching digital humanities projects to write and talk about is how esoteric and historical in nature most of them are like Maria Popova’s list of project that included “Salem Witch Trials of 1692” and “London Lives from 1690 to 1800” or Alan Liu’s list that included “Geoparsing 19th-Century Travel Narratives.”

I was looking for something more contemporary and relatable and immediately useful. A Google search returned more of the same from institutions across the world, including a project called “Creating immersive, interactive environments for engaging with ancient Egyptian coffins.” This is not a topic I want to spend any of my time exploring.

Although in my last blog post I embraced the “big tent” of digital humanities, in practice, writing about digital humanities projects or anything related to the field is challenging when there’s no clear definition. I went outside of the course recommendations to an area I’m familiar with: the law & justice sector. There were a few options I could explore and chose the National Eviction Map project from the Eviction Lab program. I figured this relates to one of the focuses of our curriculum: Data Visualization and Mapping and thus would qualify as a digital humanities project.

The majority of poor renting families in America spend over half of their income on housing costs, and eviction is transforming their lives. Yet little is known about the prevalence, causes, and consequences of housing insecurity.

Enter the Eviction Lab – a team of researchers, students, and website architects who believe that a stable, affordable home is central to human flourishing and economic mobility.

Drawing on tens of millions of records, the Eviction Lab at Princeton University published the first ever dataset of evictions in America, going back to 2000. Their goal is for the data to be used by policymakers, community organizers, journalists, educators, non-profit organizations, students, and citizens interested in understanding more about housing, eviction, and poverty in their own backyards.

Now about the DH project that is the National Eviction Map : Eviction cases are civil lawsuits filed by landlords to remove tenants from rental properties or collect past-due rent. Records of eviction cases are typically held in electronic case management systems or paper files in the local court where the case was filed. The mapping project used three strategies to collect eviction case data: bulk requests for electronic records from all state courts, requests for aggregated counts of eviction filings at the county level, and the purchase of proprietary individual records data from LexisNexis Risk Solutions. Researchers can use the data to help document the prevalence, causes, and consequences of eviction and to evaluate laws and policies designed to promote residential security and reduce poverty.

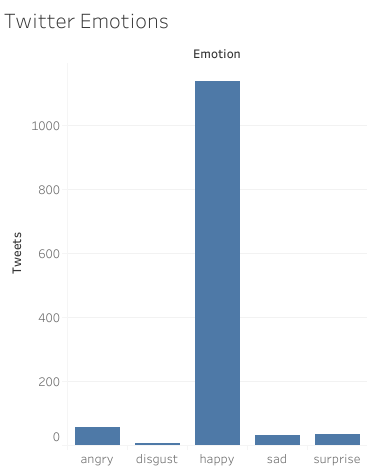

Eviction Lab has a Twitter account @evictionlab with over 12K followers with the tagline: The Eviction Lab is helping neighbors and policymakers understand the eviction crisis. In July 2022 they put out a Twitter thread about the new edition of the Map. News outlets regularly site the lab and the map when reporting on eviction-related issues.