This week’s readings cement a concept that is not as obvious as it might sound: facts are a matter of perspective. Similarly, history is a matter of perspective.

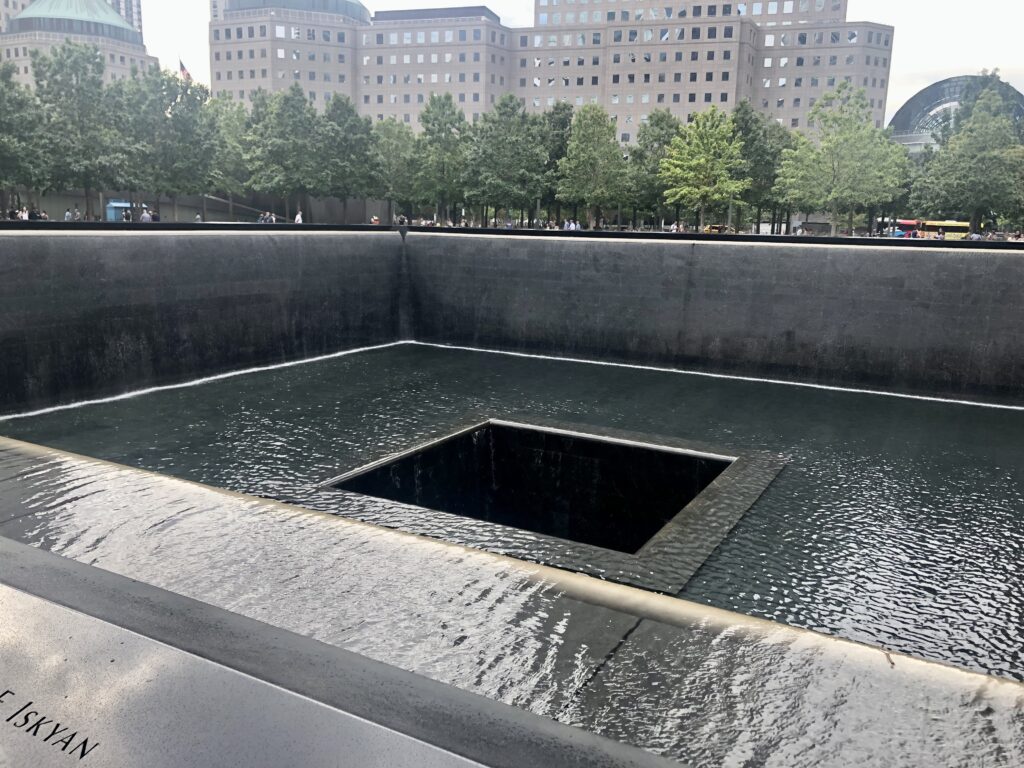

An event, any event, can be subjected to a myriad of different narrations, which could be considered veritable if accounting for the storyteller’s background and their angle. Acknowledging this without attempting to arrogate the right of divulging a universal truth is no easy task though. In this sense, the 911 Digital Archive project plays a key role in preserving history as collected from its sources. And with a great sense of acceptance in doing so, which translates into the ability of understanding, and consequently embracing, how everyone lived the same tragic day in different ways.

In this sense, Brier and Brown, in their publication The September 11 Digital Archive, stress the speed at which a system aimed at gathering as many testimonies as possible, both in digital and analog formats, had to be brought to life within days from the attack.

The authors try to go beyond what mainstream media institutions present and ask themselves the question of what consequences the 9/11 attacks generated in everyone’s life including, if not especially, the one of “ordinary” people who were either at work or going to work, those who were floating around the area of the impact, maybe spending the day somewhere in New York City or perhaps somewhere else farther, and others, who were not necessarily on site, but happened to receive a message from someone somehow directly involved.

Their idea of collecting materials, in any form or shape, and from everyone, directly and indirectly, is remarkable, and, in a sense, avant-garde. The concept revolves around the action of gathering testimonies and evidence when facts happen as opposed to wait for them to be brought together by the media or through ‘post-mortem’ research. In this light, the introduction of the role of the archivist-historian is revolutionary, and orbits around the notion of perspective and the creation of a 360-degree viewpoint, or collective history, where everybody has the right, and the channels, to actively contribute.

A similar project is carried out by the curators of Our Marathon, an online accessible archive of photos, stories, and videos of the 15th of April 2013 Boston attack. Once again, the ‘game changer’ is the authors’ modus operandi whose goal is to ensure that the contributions to the platform are crowdsourced and free from potential media manipulation.

Using this approach, new tools to accurately build a collective and democratic history have become progressively available. Platforms like Omeka, CUNY Digital History Archive, and Home – Mukurtu CMS allow everyone to share their experience and perspective. The value of this relatively new way of operating when building archives is immense and, undoubtedly, grows over time. Personally, I feely lucky to live in an era where I am given the opportunity, and the means, to contribute to history with my own experiences and angle. Unlike my grandparents, who were both sent abroad to fight during WWII and witnessed the war’s atrocities, I know I have the luxury of crystallising (and sharing) my day-to-day life and views through the internet and its endless devices, whereas their legacy, and their days in Greece, Germany and Russia, only live in my memory and might soon get lost.

Great question, Gemma -Is there a golden source?

It’s been a central theme of my thinking so far with DH.

I agree that getting to a universal truth is no easy task, and DH should be about discovering paths to get there. However, sometimes with our readings, I feel that DH makes getting there more complicated than it needs to be. This keeps the status quo of, for want of a better word, ‘western’ methods. For my end-of-term paper, I want to show how some of these universally accepted standards – ones that hardly anyone questions – are, in fact, flawed.

One area we’ve briefly explored that I believe can compete with established sources is art. For instance, if an injustice is essential enough to be passed down through generations, an artistic interpretation of that injustice is powerful. However, I think it’s vital that such work can be easily understood or explained. Johanna Drucker may be attempting to convey something like this, but her work is too abstract to be a reliable source. And we should be cautious when delving into these open-to-interpretation theoretical works so we don’t give off an air of academic elitism.

Another thing that I find more often than not in our readings is a quickness to throw the baby out with the bathwater, so to speak. Take the idea of decolonizing the narrative. I get it in principle, but how much decolonizing is enough? We first need to consider, and it might not be pleasant to acknowledge, that colonization was, in some ways, beneficial to the colonized. If we can objectively separate the good from the bad, our work will be more meaningful. In this week’s reading ‘Toward slow archives,’ it says that – “the long arc of collecting is not just rooted in colonial paradigms; it relies on and continually remakes those structures of injustice through the seemingly benign practices and processes of the profession.” But as you read through the article, it’s hard to ignore that the most reliable source of collecting Indigenous American stories from 1890 was a tool of the colonizers: Thomas Edison’s cylinder phonographic recorder. Actually hearing native voices from back then is arguably a better source of collecting than something like an oral history.

Regarding the 911 Digital Archive from this week’s readings, I agree with you when you say: the “project plays a key role in preserving history as collected from its sources.” Yet, at the start of the piece, the authors insert a political opinion: “After September 11, everything was different. This phrase became the mantra employed to justify nearly every action taken by the Bush administration in the aftermath of the attacks in New York, Washington, D.C., and Shanksville, Pennsylvania — whether the circumstances had anything to do with the attacks or not.” With the project’s goal to collect, preserve, and present significant aspects of September 11, starting with a statement about the Bush administration blurs the water. I’d probably agree with the authors, but that should be irrelevant. Say someone supported the Bush administration’s actions post 9/11; they are less likely to see the work as a reliable source of information about the tragedy.

If DH can move people closer to a golden source, alienating people or preaching to the choir should be avoided.